Control Strategies for Physically Simulated Characters Performing Two-player Competitive Sports

Jungdam Won, et. al., Facebook AI Research, USA, 2021.

ACM Digital ArchiveDirect PDF

Blog by Hanbie Ryu, 2024

Dept. of AI, Yonsei University

This paper demonstrates a novel training method for agents to perform competitive sports like boxing or fencing with human-like motion. Although this is directly related to my research area of interest, I'm not at a professional enough level to provide deeper insight than a brief, superficial overview. This is just my interpretation and breakdown of the research, intended for a broader audience. Enjoy!

Ps, Two-Minitue-Papers on YouTube did a fantastic review of this paper, showcasing the training results in depth.

We will divide this blog into the following sections:

Index:

- 1. Theoretical Background and Need for Research

- 2. Training Procedure

- 3. Preserving Movement Style During Competitive Optimization

- 4. Results and Analysis

- 5. Conclusion

1. Theoretical Background and Need for Research

1.1 What is Reinforcement Learning?

Reinforcement Learning (RL) is a type of machine learning where an agent learns to make decisions by taking actions in an environment to maximize cumulative rewards. Unlike supervised learning, where the model learns from labeled examples, RL learns from the consequences of actions, using trial and error to discover which actions yield the most reward.

Key Components of RL:

- State (\( S_t \)): The current situation of the agent in the environment at time \( t \).

- Action (\( A_t \)): The set of possible actions the agent can take in state \( S_t \).

- Policy (\( \pi \)): A strategy used by the agent to decide the next action based on the current state.

- Reward (\( R_t \)): The immediate return received after taking an action.

- Value Function (\( V(s) \)): The expected cumulative future reward starting from state \( s \).

- Action-Value Function (Q-Value, \( Q(s, a) \)): The expected cumulative future reward starting from state \( s \), taking action \( a \), and thereafter following policy \( \pi \).

Policy (\( \pi \)):

The policy is a mapping from states to probabilities of selecting each possible action. It can be deterministic or stochastic.

Deterministic Policy: \[ \pi(s) = a \]

Stochastic Policy: \[ \pi(a|s) = P[A_t = a | S_t = s] \]

Value Function (\( V^\pi(s) \)):

The value of a state under policy \( \pi \) is the expected return when starting from state \( s \) and following \( \pi \) thereafter: \[ V^\pi(s) = \mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ \sum_{k=0}^\infty \gamma^k R_{t+k+1} \bigg| S_t = s \right] \]

where \( \gamma \) is the discount factor, \( 0 \leq \gamma \leq 1 \), which determines the importance of future rewards.

Action-Value Function (\( Q^\pi(s, a) \)):

The expected return after taking action \( a \) in state \( s \) and thereafter following policy \( \pi \): \[ Q^\pi(s, a) = \mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ \sum_{k=0}^\infty \gamma^k R_{t+k+1} \bigg| S_t = s, A_t = a \right] \]

Optimal Policy and Value Functions:

The goal in RL is to find an optimal policy \( \pi^* \) that maximizes the expected return from each state: \[ V^*(s) = \max_\pi V^\pi(s) \] \[ Q^*(s, a) = \max_\pi Q^\pi(s, a) \]

1.2 Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)

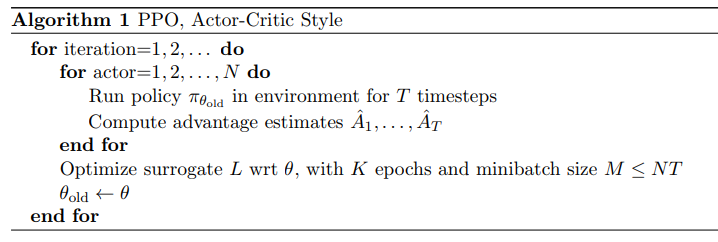

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) is a reinforcement learning algorithm that optimizes policies using gradient ascent while preventing large, destabilizing updates by clipping changes to stay within a safe range. This approach ensures each policy update is close to the previous one, enhancing training stability and efficiency.

This research used PPO for training agents in high dimensional, continuous spaces. So, how does it work?

Policy Gradient Theorem:

The policy gradient is given by: \[ \nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a|s) \, A^\pi(s, a) \right] \]

where \( A^\pi(s, a) = Q^\pi(s, a) - V^\pi(s) \) is the advantage function, representing how much better action \( a \) is compared to the average action at state \( s \).

PPO Objective Function:

PPO seeks to maximize the following surrogate objective: \[ L^{CLIP}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_t \left[ \min \left( r_t(\theta) A_t, \text{clip}(r_t(\theta), 1 - \epsilon, 1 + \epsilon) A_t \right) \right] \]

where: \[ r_t(\theta) = \frac{\pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(a_t|s_t)} \]

- \( \theta \): Current policy parameters.

- \( \theta_{\text{old}} \): Policy parameters from the previous iteration.

- \( \epsilon \): A hyperparameter that controls the clipping range.

- \( A_t \): Advantage estimate at timestep \( t \).

The clipping in the objective function prevents the new policy from deviating too much from the old policy, which helps stabilize training.

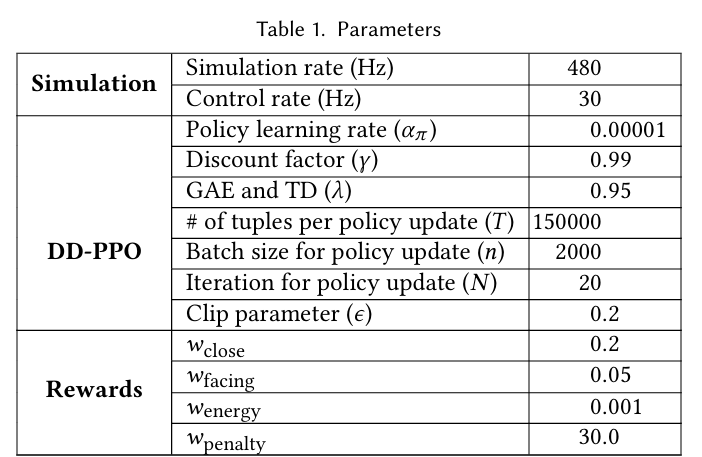

The authors utilized DDPPO (Distributed, Decentralized PPO) for computation and resource efficiency.

Why PPO?

PPO strikes a balance between value-based methods and policy gradient methods, offering the following advantages:

- Improved training stability through the clipped objective function.

- Sample efficiency by reusing data from multiple epochs.

- Simple implementation compared to other algorithms like Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO).

1.3 Training Agents to Act Realistically

The goal is to train agents that not only perform tasks effectively but also exhibit human-like motion. This is crucial in simulations and games where realistic movement enhances user experience.

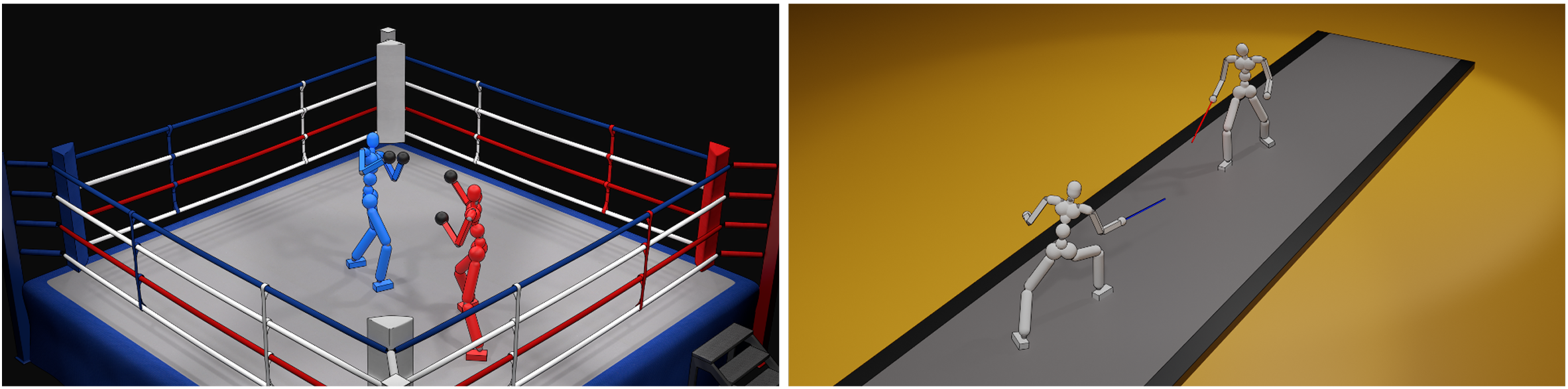

The paper uses motion capture data from CMU Motion Capture Database for boxing motion training data, totaling around 90 seconds.

1.4 Competitive Agents

Training agents for competitive environments introduces additional challenges, as having multiple competing agents means the agent's target is non-stationary.

2. Training Procedure

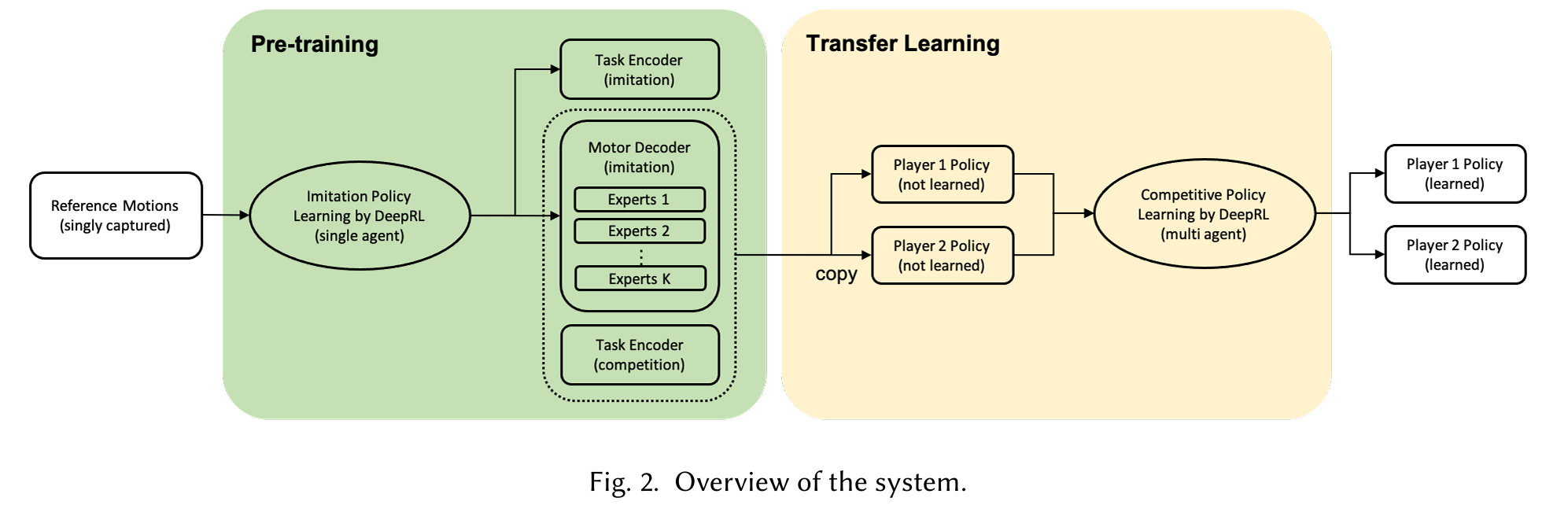

This research uses a two-step approach:

- Pre-training Phase: Trains the agent to behave like the experts from the motion-capture training data.

- Transfer Learning Phase: Trains the model to maximize competitive rewards, such as scores and penalties in boxing.

We copy only the motor decoder part of the policy when transitioning to the Transfer Learning Phase.

The agent's state is composed of:

- Body State: Holds the current positions, velocities, and angular velocities of every joint in the body.

- Task-Specific State: Contains different, appropriate states for each training phase.

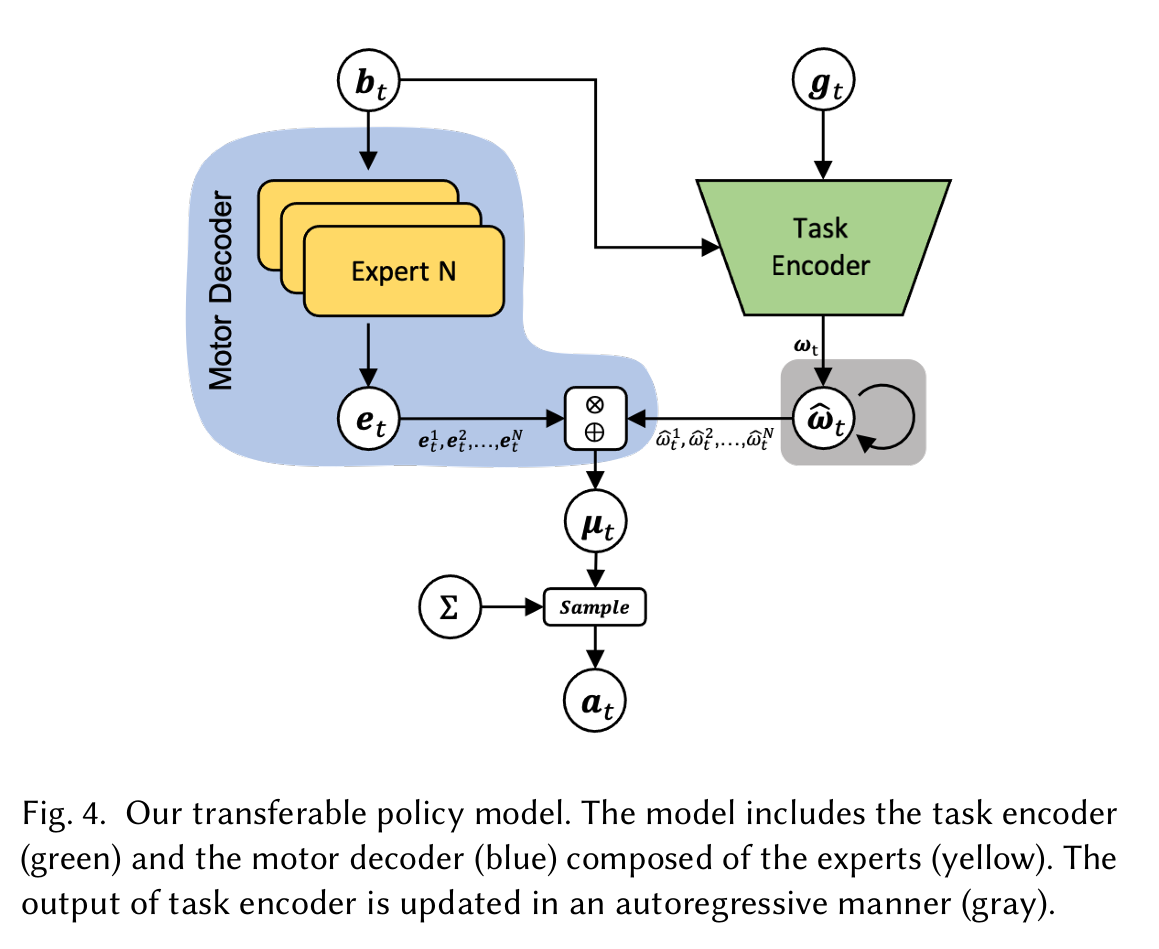

The motor decoder provides a set of outputs from the experts:

\[ e_t = \left( e_t^1, e_t^2, \dots, e_t^N \right) \]

The task encoder receives the whole observed state as input and generates expert weights:

\[ \omega_t = \left( \omega_t^1, \omega_t^2, \dots, \omega_t^N \right) \]

The weights are updated in an autoregressive manner to ensure smooth transitions:

\[ \hat{\omega}_t = (1 - \alpha) \omega_t + \alpha \hat{\omega}_{t-1} \]

where \( \alpha \) controls the smoothness of the weight change.

The mean action \( \mu_t \) is computed as a weighted sum of the experts’ outputs:

\[ \mu_t = \sum_{i=1}^N \hat{\omega}_t^i e_t^i \]

The final action \( a_t \) is sampled from a Gaussian distribution with mean \( \mu_t \) and covariance \( \Sigma \):

\[ a_t \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_t, \Sigma) \]

where \( \Sigma \) is a constant diagonal matrix representing the covariance.

In other words, the Motor Decoder produces expert motions that would follow the current state of the body, and the Task Encoder creates a combination of those motions, which is key in creating realistic movements for a given task.

2.1 Pre-training Phase

The task-specific state holds motion sequences 0.05s and 0.15s into the future, with imitation rewards encouraging the agent to imitate the training motion data, producing realistic human-like movement.

2.2 Transfer Learning Phase

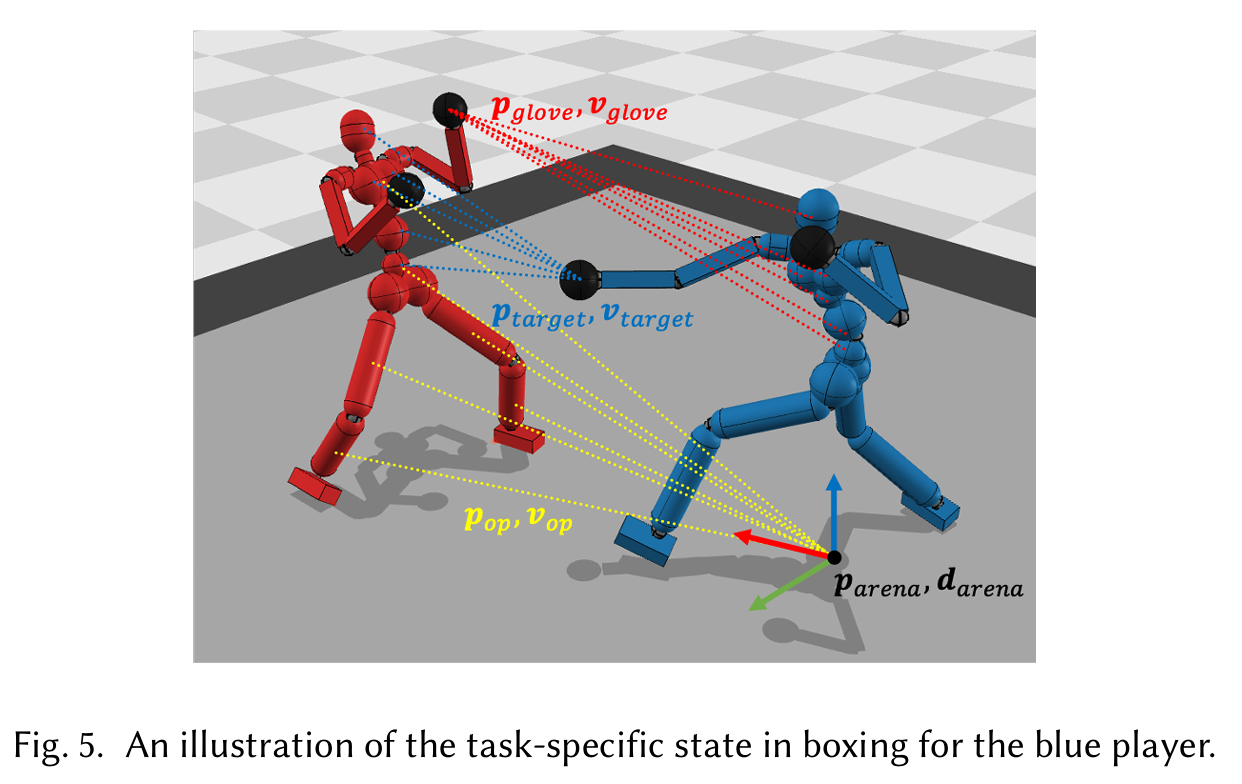

The task-specific state holds relative target positions of the opponent agent and other variables needed to maximize competitive rewards.

\[ g_t = (p_{\text{arena}}, d_{\text{arena}}, p_{\text{op}}, v_{\text{op}}, p_{\text{glove}}, v_{\text{glove}}, p_{\text{target}}, v_{\text{target}}) \]

The rewards here are a weighted sum of:

- Match Rewards: Calculates the normal force of the punches between each agent and computes the force applied to the opponent minus from the agent.

- Closeness Rewards: Encourages the agents to be close to each other, increasing the likelihood of competitive action occurring.

- Facing Rewards: Encourages the agents to face each other. Without this, agents might punch each other in the back, which rarely happens in real life.

- Energy Rewards: Penalizes excessive motor use, encouraging the agents to move more efficiently (although, it is noted that removing this term leads to more dynamic and entertaining results) .

- Various Penalties: Terminates the episode if one of the agents loses balance and falls to the ground, or if the agents get stuck between each other or on the ropes.

Reward function:

\[ r = r_{match} + w_{close} r_{close} + w_{facing} r_{facing} - w_{energy} r_{energy} - w_{penalty} \sum_{i} r^{i}_{penalty} \]

where:

- \( r_{match} \):

- \( r_{close} \):

- \( r_{facing} \):

- \( r_{energy} \):

- \( r^{i}_{penalty} \):

\[ r_{match} = \| f_{pl \rightarrow op} \| - \| f_{op \rightarrow pl} \| \]

\[ r_{close} = \exp(-3d^2) \]

\[ r_{facing} = \exp(-5\| \bar{v} \cdot \hat{v} - 1 \|) \]

\[ r_{energy} = \kappa_{dist} \sum_{j} \| a_j \|^2 \]

\[ \kappa_{dist} = 1 - \exp(-50\| \max(0, l - 1) \|^2) \]

\[ r^{i}_{penalty} = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if the condition is satisfied} \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \]

In transitioning from the Pre-training Phase to the Transfer Learning Phase, only the Motor Decoder is reused. This means it still produces human-like expert motions that follow a given body state, and only the weights for their combination are reinitialized.

The Task Encoder is then trained with an opponent agent, learning to adaptively weigh the expert actions generated by the Motor Decoder based on the competitive context. It computes a set of weights for each expert action, emphasizing particular movements (e.g., attacking, dodging, blocking) depending on the opponent’s location and posture.

In essence, the Task Encoder serves as a strategic component, dynamically adapting the expert motions produced by the Motor Decoder to match real-time competitive needs, ensuring that each movement looks both realistic and purpose-driven.

3. Preserving Movement Style During Competitive Optimization

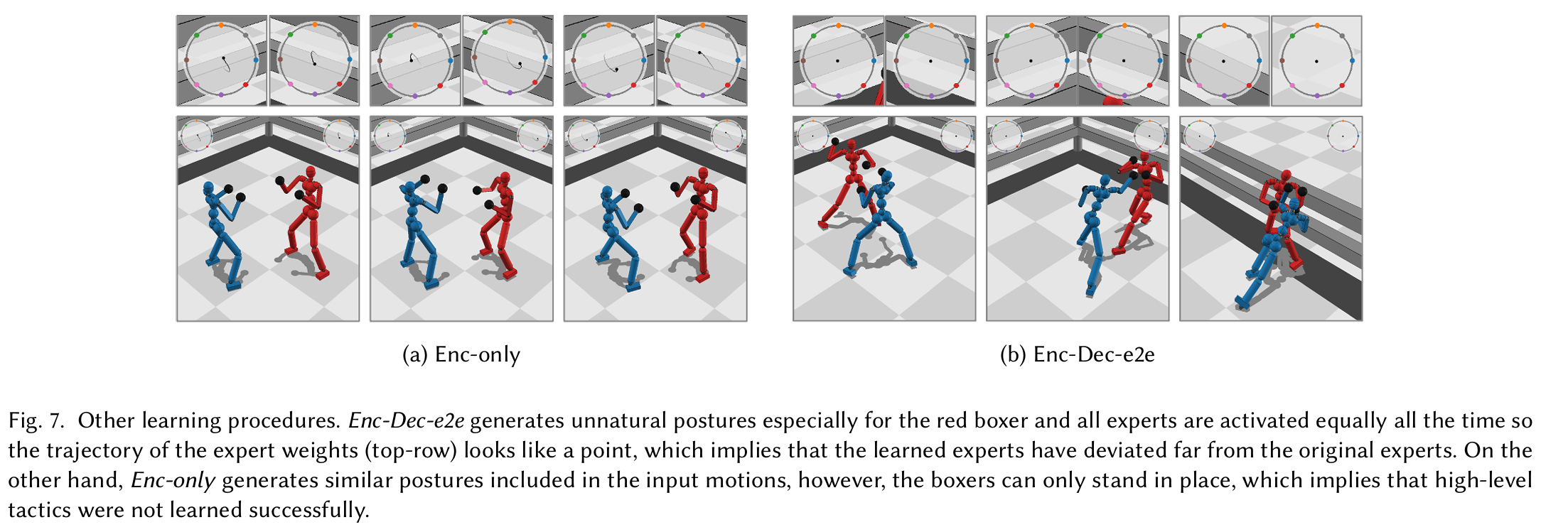

The Motor Decoder provides important motor information to the agent, but it may not be optimized for the task, leading to suboptimal results when the Motor Decoder parameters are fixed during Transfer Learning (Enc-only).

On the other hand, if the Motor Decoder parameters are optimized together with the Task Encoder parameters (Enc-Dec-e2e), it could lead to maximal competitive rewards, but the learned expert movements might be "forgotten" during optimization.

This is why, in the research, they alternate between Enc-only and Enc-Dec-e2e learning to preserve the pre-trained movements during competitive optimization. Specifically, they start with Enc-only for 300-500 iterations, then alternate every 50 iterations. This alternating training method provides a fine balance between movement preservation and task optimization.

4. Results and Analysis

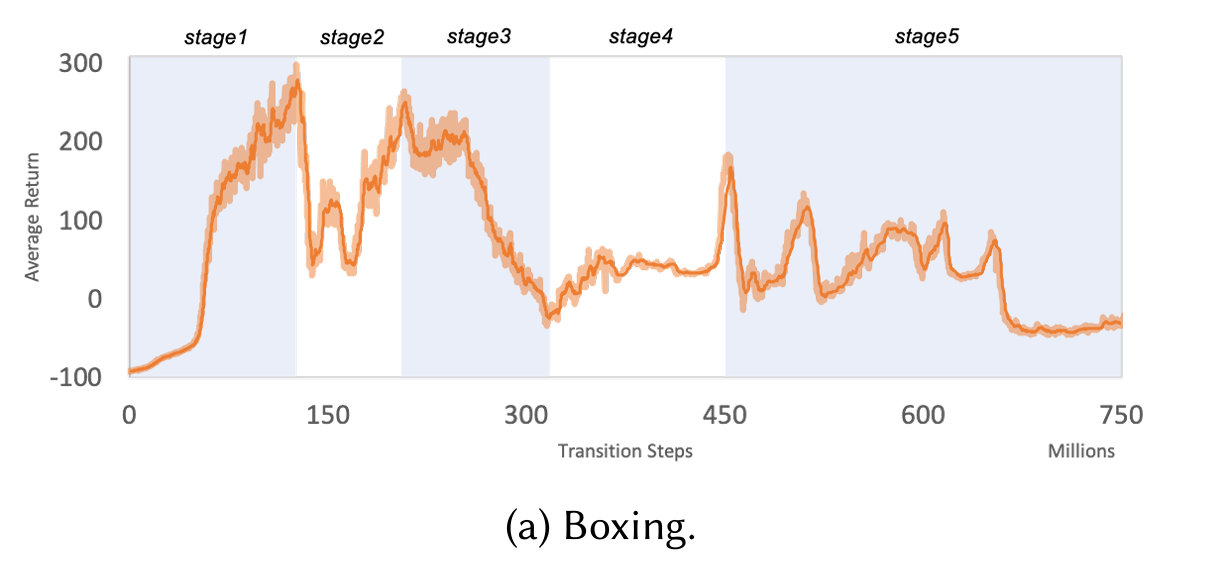

Since the agents have competitive rewards, we can expect them to follow a sort of zero-sum game. From the paper's observation, we divide the training curve into 5 stages:

- Stage 1: Cumulative rewards increase as the agents learn to stand up correctly.

- Stage 2: Unintended collisions occur.

- Stage 3: Agents develop punching abilities; rewards decrease towards zero.

- Stage 4: Agents develop blocking and avoiding punches; rewards bounce back.

- Stage 5: Fluctuates between Stage 3 and 4.

At Stage 5, the paper judges that the policy converges when the match rewards are around zero during this stage.

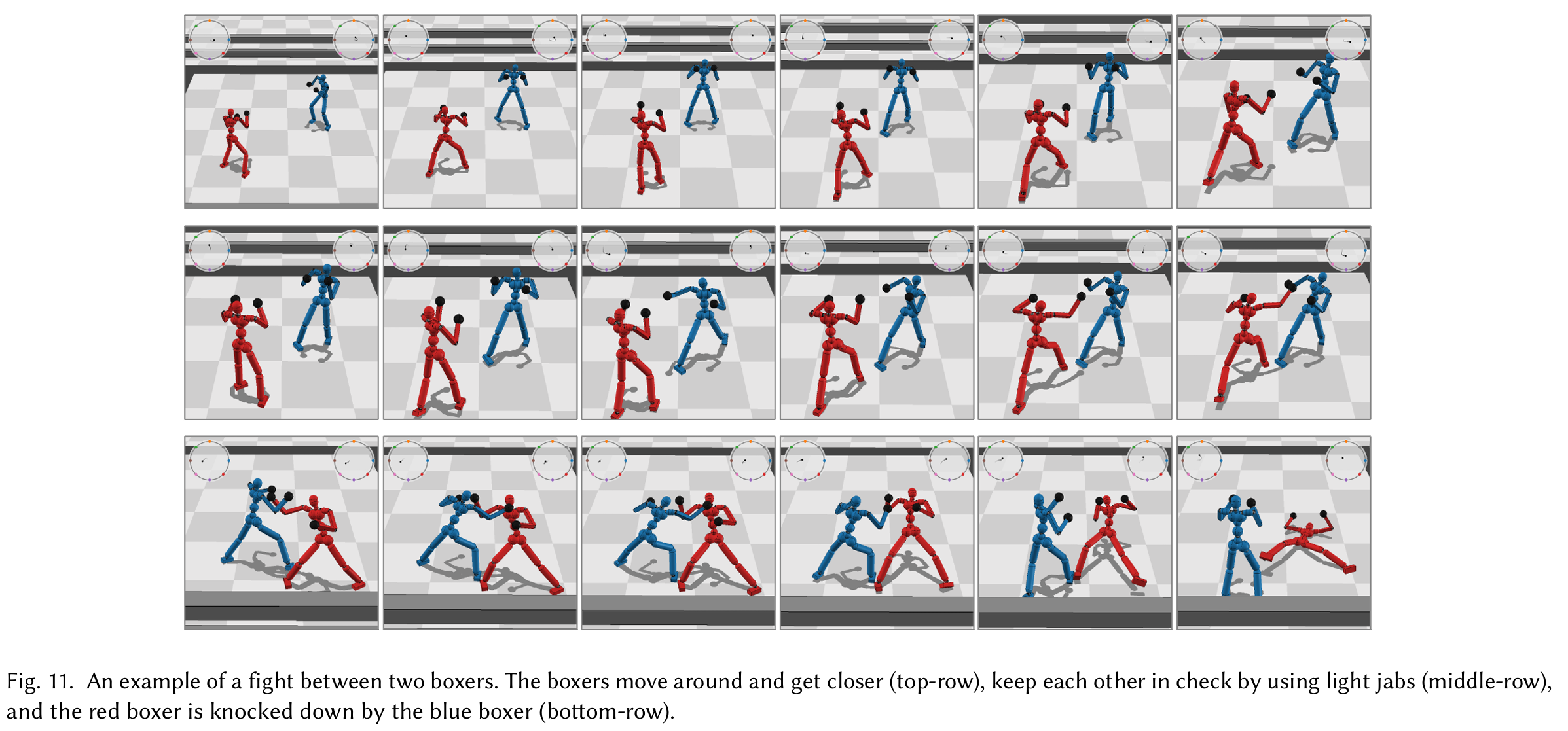

The agents are shown to successfully throw jabs at the oponent at 1B steps.

Similar results are shown in fencing, where the agents learned to strike the opponent and make counter attacks.

Additionally, the researchers also tried different movement experts, this one mimicing gorillas

5. Conclusion

This paper illustrates the effectiveness of combining a Pre-training Phase with a Transfer Learning Phase to train agents with realistic, adaptive, and competitive behaviors.

- Realistic Motion: The two-phase approach enables agents to produce lifelike movements through pre-training on motion capture data, enhanced by autoregressive smoothing in the Task Encoder.

- Adaptive Competitive Behavior: In the Transfer Learning Phase, agents dynamically adjust actions based on opponent movements, balancing offense and defense with strategic depth.

- Diverse Styles: By tuning expert weights, the Task Encoder enables varied movement styles, allowing agents to adopt distinct strategies, enhancing realism in competitive settings.

- Quantitative Gains: Metrics like competitive rewards improved significantly post-transfer learning, showcasing the model’s effectiveness compared to baseline models without pre-training.

- Challenges: Agents faced limitations with unexpected opponent behavior, highlighting areas for reward structure tuning to balance aggression and defense.

- Broader Applicability: The framework’s potential extends to simulations and games, offering human-like animations and behaviors for interactive sports and training scenarios.

In conclusion, this research demonstrates that integrating imitation learning with reinforcement learning produces competitive agents with fluid and nuanced behaviors, offering valuable applications in fields that require adaptive, realistic virtual characters.